History

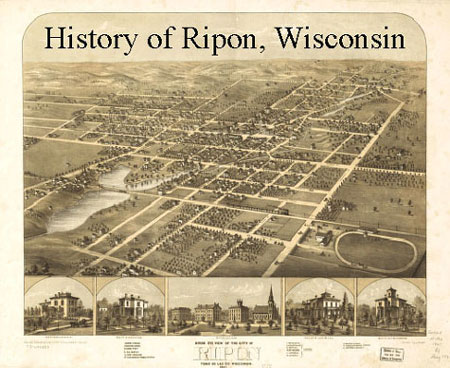

Ripon's rich history began with a group of 19 Wisconsin Phalanx settlers interested in establishing a community based on Charles Fourier's principles of social philosophy.

View Ripon Historical Society Facebook Page

On May 27, 1844, they founded "Ceresco," named after the Roman goddess of the harvest. Soon, more than 200 idealists came to Ceresco and constructed several homes, or long houses, where they lived together as large groups. One of the long houses still stands on its original site. For five years the Fourierites prospered to an extent greater than those in most utopian socialist experiments. To this day, this area continues to be called Ceresco.

On May 27, 1844, they founded "Ceresco," named after the Roman goddess of the harvest. Soon, more than 200 idealists came to Ceresco and constructed several homes, or long houses, where they lived together as large groups. One of the long houses still stands on its original site. For five years the Fourierites prospered to an extent greater than those in most utopian socialist experiments. To this day, this area continues to be called Ceresco.

For two years, a rivalry flourished between Warren Chase and David P. Mapes who arrived in 1849, over the future of their adjacent communities. It soon became apparent that Ceresco would not survive, and the Phalanx Corporation dissolved, disposing of its property and dividing up its substantial profits in 1851. The six-year experiment had been an economic success, but a social failure.

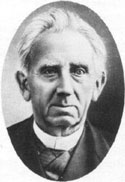

In 1849, Captain David P. Mapes (pictured at left) arrived in the area and fell in love with a "silver creek weaving its way through Wisconsin's rolling hills." He built a grist mill on the hill and with John Scott Horner who owned part of the nearby land, suggested the newly created settlement be named "Ripon" in honor of his ancestral home, the English cathedral city of Ripon, Yorkshire.

In 1849, Captain David P. Mapes (pictured at left) arrived in the area and fell in love with a "silver creek weaving its way through Wisconsin's rolling hills." He built a grist mill on the hill and with John Scott Horner who owned part of the nearby land, suggested the newly created settlement be named "Ripon" in honor of his ancestral home, the English cathedral city of Ripon, Yorkshire.

For more than a decade, Mapes labored to develop his community: building a flour mill and a public house, donating lots to prospective settlers who would agree to establish places of business on the square, obtained railroad trackage south to Milwaukee and north to the Wolf River, and persuaded the Federal Government to move the post office from the nearby community of Ceresco to Ripon.

In order to induce settlers to locate in Ripon, Mr. Mapes gave away lots upon condition that the recipients would make certain improvements to the community or erect specified buildings before a certain time. The first lot was given to E.L. Northrup, who built Ripon's first store. After 1850, Ripon, having a mill, hotel, post office, blacksmith-shop and several stores, attracted many settlers and grew rapidly.

Alan Earl Bovay (pictured at right) arrived just as the Phalanx was disbanding, but Mapes persuaded Bovay to cast his lot with the emerging Village of Ripon. So he purchased land in the 400 block of Watson Street and began developing "Bovay's Addition" to the village. As one of the town's first lawyers, Bovay played an important role in Ripon's growth into a city. As a political reformer with strong Whig Party connections in the East, he took a leading part in the famous 1854 meeting in the Little White Schoolhouse, where the Republican Party was formed.

Alan Earl Bovay (pictured at right) arrived just as the Phalanx was disbanding, but Mapes persuaded Bovay to cast his lot with the emerging Village of Ripon. So he purchased land in the 400 block of Watson Street and began developing "Bovay's Addition" to the village. As one of the town's first lawyers, Bovay played an important role in Ripon's growth into a city. As a political reformer with strong Whig Party connections in the East, he took a leading part in the famous 1854 meeting in the Little White Schoolhouse, where the Republican Party was formed.

By an act approved April 2, 1853, the villages of Ceresco and Ripon were consolidated and named Morena. The inhabitants, however, paid little attention to this change. Instead, they retained the original name; incorporating as the City of Ripon in 1858.

On the evening of March 20, 1854, a group of people met in a small frame schoolhouse to protest the opening of the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery. Disgusted with the failure of existing political parties and the U.S. Congress to uphold the cause of freedom in the West, they formed a new antislavery party and called it Republican. They came out of the schoolhouse in agreement that one unified front was crucial to the fight against slavery and thus began the Republican Party. "We went into the little meeting held in a school house Whigs, Free Soilers, and Democrats. We came out of it Republicans and we were the first Republicans in the Union," wrote Alan E. Bovay. It was his friend, Eastern newspaper publisher Horace Greeley, who boosted the name to national prominence.

The dates of construction of the buildings in the historic district reflect the significant amount of reconstruction that took place in the downtown after disastrous fires wiped out almost two whole blocks of frame constructed commercial buildings in 1868 and 1869 and other fires that took out a number of buildings during the 1870s and 1880s. Little construction took place in the district after 1890, except in the 300 block of Watson Street, where the commercial business district was stretching to its limits.

Much of historic downtown Ripon remains intact, having changed little over the last 125 years. In a time when some communities lost entire blocks of buildings to the urban renewal effort of the 1970s, the Watson Street National Commercial Historic District remains relatively unchanged. In addition, greater appreciation of our architectural heritage has resulted in a growing number of these buildings being preserved and accurately restored rather than being demolished or modernized beyond recognition.

Much of historic downtown Ripon remains intact, having changed little over the last 125 years. In a time when some communities lost entire blocks of buildings to the urban renewal effort of the 1970s, the Watson Street National Commercial Historic District remains relatively unchanged. In addition, greater appreciation of our architectural heritage has resulted in a growing number of these buildings being preserved and accurately restored rather than being demolished or modernized beyond recognition.

Ripon also boasts other historic districts. The residential area south of the downtown has many magnificent, fully restored Victorian Painted ladies, with architectural styles ranging from Italianate and Queen Ann to Second Empire and Greek Revival.

Ripon College, a private liberal arts college, is just west of the business district. In 1851, David Mapes and a group of townspeople founded the college on top of the hill, chartered on January 29, 1851 as Brockway College. Mapes, who was president of the first board of trustees, donated an acre of land on the highest point in the village of Ripon. To raise money for the college, the trustees issued stock and offered to name the institution after the person who bought the largest amount. William Brockway took the honor with just over $300 in stock and the school was incorporated as Brockway College. In 1864 the name was changed to Ripon College.

Check out Ripon's walking or online interactive historic tour!

Ripon's Mystery Cave

In June 2001, Ripon Main Street and Wisconsin Speleological Society (WSS) members dug under the former Bread Basket Bakery. Borings revealed a void under the concrete basement floor. A week later, volunteers broke open the floor, creating a 4-foot opening – "The Pit." (Photo)

The building that covers The Pit served as a bakery for more than 40 years until the late 1990s when fire caused heavy damage and forced it out of business. Prior to the bakery, the building housed numerous butcher shops going back as far as the 1870s. WSS member Karl Ziebert said he heard stories from local old-timers who recall working at the butcher shop and using it to dispose of meat waste products. Ripon historian George Miller said he remembers hearing stories about meat products being thrown into the pit and being washed into Silver Creek, located two blocks north of the building.

The Pit is a round opening that was filled with sand, rock and coal ash. Probing rods indicated the hole extended at least 8 feet down. The north half of the hole is made of a hand-laid stone. The south side is a dolomite cliff that plunges to the bottom of the hole. (Photo)

Underground Railroad?

Ripon Main Street and WSS began excavation of the hole because of stories dating back several generations about underground passages located beneath Ripon's downtown. Rumors indicated that pre-Civil War slaves accessed the passages as they fled north to freedom.

Stories of runaway slaves seeking refuge in Ripon have circulated for decades. Some call these stories rumors, but there is documented proof that slaves hid in some buildings in Ripon during their escape to Canada. Officials at the Wisconsin Historical Society, however, report that slaves were not likely hidden in this underground site. The major routes of the railroad, they said, started at the southwest tip of the state and headed to Milwaukee or up the Mississippi River, not into Ripon.

Still, many residents of Ripon wonder if The Pit was as some point a hidden passageway to freedom.